Intento de tornaviaje de la Trinidad

Por qué la Trinidad y la Victoria se separan

La nao Trinidad, capitana de la expedición, zarpó inicialmente de las Molucas bajo el mando de Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa el 18 de diciembre de 1521 junto con la Victoria de Elcano. Sin embargo, nada más salir de Tidore empezó a hacer agua y, pese a la ayuda de buzos moluqueños, no tuvieron más remedio que descargarla por completo para averiguar dónde estaba la avería. Una vez fue localizada, se comprobó que la nave necesitaba de reparaciones importantes en el casco.

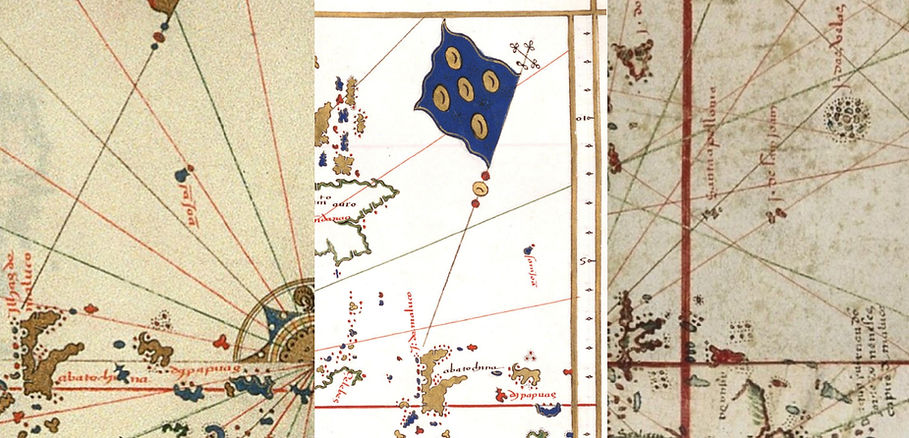

Detalle del mapamundi del cosmógrafo jefe de la Casa de Contratación de Sevilla, Diego Ribero, del año 1529. En él vemos la nao Trinidad en el Pacífico Norte, y bajo de ella escrito "vuelvo a Maluco". El texto de arriba dice así: "Esta es la nao trinidad que queriendo venir a la mar del Sur subió hasta 42 grados por hallar tiempos contrarios y de allí se volvió a Maluco otra vez por que hacía ya 6 meses que andaba a la mar y hacía agua y le faltaron mantenimientos."

Ribero pudo conocer en Sevilla al capitán Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa tras la vuelta de éste a España, y tener noticia de primera mano de su odisea.

Se dieron cuenta de que iban a necesitar varios meses para conseguir poder zarpar de nuevo, y esto era un doble problema. Por un lado, los nativos hablaban de que ese era el momento en que debían zarpar hacia el Oeste por contar con vientos favorables, pero además, el portugués Pedro Alfonso de Lorosa, apareció por allí durante esos días y dio el aviso de que en cualquier momento podrían llegar los suyos, que sin duda tratarían por la fuerza de impedir el éxito de los españoles.

Ante esta situación, la Victoria zarpará, iniciando su camino de vuelta a España y quedando en Tidore la nao Trinidad y 59 ó 60 hombres. Leamos a los propios protagonistas que estuvieron allí lo que nos cuentan de este momento:

-

Queriéndonos partyr de las yslas de Maluco a la vuelta de España, descobrió una agua muy grande una de las dos naos de manera que no se podía remediar sin ser descargada, e pasado el tienpo de [que] las naos navegaba[n] para Jaba e Malaca, determinamos de morir o con grande honra a serviçio de tu alta magestad, por haserla sabidora del dicho descobrimiento, con una sola nao partyr estando tal de bromas como Dios quería. Carta de Juan Sebastián del Cano al Rey, fecha en Sanlúcar de Barrameda el 6 de septiembre de 1522.

-

Y resolvimos mandar adelante a la nave Victoria, para que no perdiese tiempo y llevase las nuevas al Rey mi señor, y nosotros quedamos aquí, donde, espero en Dios, haber alistado la nave dentro de cincuenta días y venir por el Darién, donde Andrés Niño hizo las naves, y de allí por tierra firme para dar las nuevas al Rey mi señor. Carta de Juan Bautista de Punzorol a un personaje que no se nombra. Tidore, 21 de diciembre de 1521.

-

Después que la nao Victoria partió de Maluco, nos fue necesario de quedar con la otra nao. Con mucho trabajo y mucho peligro la corregimos, y estuvimos en corregilla y en cargalla de clavo cuatro meses en la isla de TIdori. Carta de Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa al Rey, fecha en Cochín a 12 de enero de 1525.

-

Estando para partir estas naos, la capitana descubrió una agua que fue menester para aderezarla tornarla a descargar, y porque no se perdiese tanto tiempo acordaron que se partiese la otra nao, y así se hizo. Relación de Ginés de Mafra, piloto de la nao Trinidad.

-

El rey [de Tidore] pareció que se afectaba vivamente con este contratiempo, hasta el punto que se ofreció él mismo para ir a España y relatar al rey lo que nos sucedía; pero le respondimos que, teniendo dos navíos, podríamos hacer el viaje con la victoria sola, que no tardaría en partir aprovechando los vientos de levante que empezaban a soplar; durante este tiempo carenarían la Trinidad, que podría aprovechar los vientos de poniente para ir a Darién, al otro lado del mar, en la tierra de Yucatán. [...] Hubo algunos que prefirieron quedarse en las islas Maluco mejor que volver a España, ya por temor de que el navío no resistiera tan largo viaje, ya porque el recuerdo de lo que sufrieron antes de llegar a las Maluco les ametrentase, pensando que morirían de hambre en medio del Océano. [...] El sábado, 21 del mes [de diciembre] día de Santo Tomás, el rey nos trajo dos pilotos, que pagamos por anticipado, para que nos condujeran fuera de las islas. Nos dijeron que el tiempo era excelente para el viaje y que debíamos partir cuanto antes; pero tuvimos que esperar a que nos trajesen las cartas que nuestros compañeros que se quedaban en las Maluco mandaban a España, y no pudimos levar anclas hasta el mediodía. Entonces, los barcos se despidieron con una descarga recíproca de artillería; los nuestros nos siguieron en su chalupa tan lejos como pudieron, y nos separamos, al fin, llorando. Relación de Pigafetta.

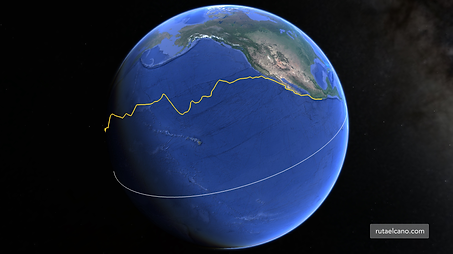

Vista en Google Earth de la derrota que con bastante probabilidad siguió la Trinidad en su intento de tornaviaje desde las Islas Molucas hasta el Darién, en el actual Panamá (línea blanca).

Lo cierto es que todos estaban en una situación muy comprometida porque lo que la Victoria pretendía hacer no era una opción claramente mejor que atravesar el Pacífico. Se iban a adentrar en la demarcación portuguesa, y para evitar ser apresados tratarían de alejarse de la costa africana en todo momento hasta llegar a España. Como planteamiento, qué duda cabe de que resulta más que audaz, casi inverosímil. Su única ventaja era que en caso de tener éxito serían los primeros en haber dado la vuelta al mundo, y eso ilusionaba a Elcano y muchos otros que le acompañaron (ver La Gran Decisión de Elcano). Así, por ejemplo, Pigafetta elige ir con Elcano en vez de quedarse con Espinosa. Lo hizo sin duda por dar la vuelta al mundo, no por afinidad con Elcano, al que ni siquiera nombra en su extensa relación del viaje.

Nao navegando de bolina. Detalle del

mapamundi de Guillaume Le Testu, de 1566.

Desgraciadamente la Trinidad no conseguió su objetivo. Encontró vientos contrarios que le impedían avanzar hacia el Este, viéndose obligada a desviar su ruta muy hacia el Norte. Llegó a alcanzar la altura del paralelo 42º N siguiendo la corriente de Kuro Siwo, pero entonces sufrió un terrible temporal, de cinco días de duración, que a punto estuvo de mandar a pique la nave y la dejó muy maltrecha. Además, las muertes motivadas por el frío y la escasez de alimentos se estaban cebando ya con la tripulación, de modo que no tuvieron más remedio que dar la vuelta para volver a las Molucas de forma muy penosa pero, esta vez sí, con vientos portantes muy favorables.

Sin embargo, durante los siete meses que durará la travesía, los portugueses habrán vuelto a las Molucas, y allí interceptarán a la Trinidad y apresarán a los ya solo 17 supervivientes. Fue una durísima travesía, a la que siguieron más de cuatro años de cautiverio y de trabajos forzosos para los cada vez menos expedicionarios.

Gráfico que muestra las muertes acumuladas durante la travesía que hizo la nao Trinidad intentando cruzar el Pacífico, y dando la vuelta de nuevo hasta las Molucas. Es evidente que cuando zarparon iban sanos y bien pertrechados, pero a partir de la tormenta que sufren el ritmo de muertes es terrorífico.

Metodología seguida para la determinación de la derrota de la nao Trinidad.

Para determinar cuál fue el camino seguido por la Trinidad no lo tenemos tan fácil como con el caso de la ruta del viaje alrededor del mundo, porque no se ha conservado el derrotero con las posiciones diarias. Sin embargo, contamos con otras fuentes que nos van a permitir investigar cuál fue la derrota seguida:

-

Carta de Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa a Carlos I, narrando las vicisitudes del periplo en solitario de la nao Trinidad por el Pacífico Norte, y su prisión por los portugueses. A.G.I., Indiferente, 1528, N.2. Enlace.

-

Interrogatorios a los tripulantes supervivientes de la nao "Trinidad", de la armada de Magallanes, sobre lo acontecido en su retorno de las Molucas. A.G.I., Patronato, 34, R.27. Enlace.

-

Probanza sobre el derecho real a las islas Molucas. A.G.I., Patronato, 49, R.4. Enlace.

-

Roteiro de un piloto genovés, original contenido en el documento llamado Livro de Duarte Barbosa e outros papéis (fols. 163 a 173). Torre do Tombo, Manuscritos do Brasil, liv. 25. Enlace.

-

Relación de Ginés de Mafra, Biblioteca Nacional de España, RES/18. Enlace.

-

Memoria de las personas que murieron en la nao Trinidad. A.G.I., Patronato, 34, R.20. Enlace.

-

Carta do mestre e piloto da nau espanhola Vitória para o Imperador Carlos V, referente à viajem que fez à ilha de Tidore, e solicitando-lhe ajuda para regressar. Torre do Tombo, Gavetas, Gav. 17, mç. 6, n.º 24. Enlace.

-

Carta de Batista de Ponçorom e Leon Pançado, dando conta dos trabalhos que tiveram numa viagem que fizeram a Maluco e como ficaram cativos dos portugueses. Torre do Tombo, Gavetas, Gav. 15, mç. 10, n.º 34. Enlace.

-

Carta dirigida ao rei de Castela com o relatório de uma viagem feita a Maluco por ocasião da qual se tinha descoberto várias ilhas duzentas léguas adiante de Maluco, que atribuimos a Juan Bautista de Punzorol y León Pancaldo. Torre do Tombo, Gavetas, Gav. 15, mç. 10, n.º 43. Ver explorahistoria.es/rareza.

Sin embargo, encontramos dificultades porque los documentos en general son imprecisos, y en algunos casos la información dada no es coherente entre sí. Además, se utilizan topónimos que, en general, nada tienen que ver con los actuales. Por otro lado, resultaría improbable que los supervivientes pudieran conservar algún documento escrito durante el viaje, es decir, que los que nos han llegado debieron ser escritos de memoria.

Los datos clave del viaje quedan resumidos así según las fuentes, y con ellos vamos a empezar a componer el puzle:

DATO Nº1: Inicio del viaje

El Roteiro y la carta de Espinosa nos dan la fecha de salida desde Tidore: el 6 de abril de 1522. No hay duda en ello.

A continuación, es en el Roteiro donde encontramos una descripción bastante detallada de las derrotas mantenidas alrededor de la isla Halmahera, la más grande del archipiélago de las Molucas, y a la que llama Betachina, hasta su llegada al puerto de Quimor, donde se detienen "8 ó 9 días". Describe con sorprendente exactitud el camino seguido hasta alcanzar una isla frente a Betachina, la isla que llama Doyz, en principio fácilmente identificable puesto que hoy se llama Doi: "Navegaron después a lo largo de la isla de Betachina al Nornoreste diez u once leguas, y después gobernaron cosa de veinte leguas al Nordeste, y así llegaron a una isla llamada Doyz."

Sin embargo, nos despista su latitud puesto que Doi está en 2º20'N mientras que dice "está en tres grados y medio". Evidentemente lo debemos tener como un error puesto que la descripción anterior del camino seguido es realmente buena, y sería inconsistente con haber alcanzado esa latitud.

Además, prosigue el relato nuevamente con detalle: "De aquí (de Doiz) navegaron al Este tres o cuatro leguas, avistando dos islas, una grande llamada Chaol, y otra pequeña, Pyliam, pasando por entre la mayor y Batechina (la llama indistintamente Batechina y Betechina) que quedaba de la banda de estribor." Nos está describiendo exactamente el paso hacia el Este desde el extremo Norte de la isla de Halmahera. Y añade: "Llegaron a un cabo, a que pusieron nombre de cabo de Ramos, porque lo avistaron en la víspera de Ramos. Este cabo está en dos grados y medio." En realidad el cabo del extremo Norte de Halmahera se encuentra a 2º11', y no hay ningún otro a mayor latitud. Esta vez sí, fue una buena aproximación para estar hecha con un cuadrante del siglo XVI.

Hasta aquí hemos llegado con un grado de incertidumbre muy bajo. Sin embargo empieza a enrevesarse el asunto, porque desde este punto dice que se dirigen al Sur, a un puerto llamado Quimor que está en un grado y cuarto, donde se abastecen de víveres y permanecen "ocho o nueve días". Si a un grado y cuarto le damos cierto margen posible de error, este puerto puede estar en muchos sitios distintos. No obstante, encontramos que en ese entorno actualmente existe una ciudad grande llamada Tobelo que de hecho es la capital de la isla, y que debemos considerar como candidata a que corresponda con Quimor. Así que atendemos cómo prosigue el texto del Roteiro:

"Partieron de este puerto a los veinte de abril, y gobernando al Este diecisiete leguas, salieron por el canal de la isla de Batechina y la de Charam, y tan luego como estuvimos fuera, vieron que la dicha isla de Charam corría al Sudeste más o menos dieciocho o veinte leguas y que estaban fuera de camino, porque el verdadero era al Oeste y cuarta del Nordeste, por lo cual, siguiendo este rumbo, navegaron varios días, hallando siempre el viento muy favorable."

De este párrafo podemos concluir que si tras salir de Quimor navegaron 17 leguas al Este, es porque esta población no se encontraba dentro del canal que podemos observar en el mapa más al Sur, ya que pasa salir del canal les habría sido necesario navegar al N-NO.

De todos modos, al tratar de profundizar sobre la posible localización de Quimor, sobre la que ni Mafra ni Espinosa hablan, encontramos un texto que nos aporta una importante pista. Se trata del Derrotero de la Expedición de Loaysa al Maluco, la siguiente expedición que el Emperador envió allí, y en la que por cierto falleció Elcano. En él leemos que la única nao superviviente a esas estas alturas, llamada Santa María de la Victoria recaló en la costa Este de la isla de Batechina (que ellos llamaban de Gilolo) y localizaron allí una ciudad importante llamada Zamafo. Dan su latitud en un grado y un tercio, que es exactamente la de la ciudad de Tobelo, y además describen la que delante de ella hay multitud de pequeñas islas, tal como podemos ver frente a Tobelo.

En conclusión, y espero no desesperar a nadie, Quimor y Zamafo con toda probabilidad son diferentes topónimos para una misma ciudad importante de la costa Este de la isla de Halmahera, también llamada entonces como de Batechina o de Gilolo, que corresponde con la actual ciudad de Tobelo.

En Quimor permanecieron "...ocho o nueve días, y allí tomaron puercos y cabras y gallinas y cocos y hava -una bebida local-. Partieron de este puerto a veinte de abril". Por fin nuestros navegantes dejan atrás las Molucas y entran en mar abierto.

DATOS Nº 2, 3 y 4: Las islas que visitaron

DATO Nº 2: Dos islotes del archipiélago de Sonsorol

El Roteiro nos sigue contando así: "Y a los tres de mayo encontraron dos islas pequeñas, que podrían estar en cinco grados." Se trata de una cita muy vaga, que nos obliga a explorar con mucho detenimiento toda esta zona del océano para localizar todos los islotes posibles. Por suerte, tras realizar esta labor no tenemos dudas: estas dos islas pequeñas las encontramos al SE de Palaos, en el pequeño archipiélago de Sonsorol. Son las únicas dos islas que encontramos juntas en una amplísima región, y además su latitud coincide con la que tenemos de referencia puesto que están en 5º20' N.

De ello podemos también concluir que desde las Molucas hasta aquí siguieron rumbo al Nordeste, es decir, ya empezaron a sufrir vientos contrarios y a tener que desviarse del camino más recto hacia Panamá.

Los dos pequeños islotes del archipiélago de Sonsorol que encontró la Trinidad el 3 de mayo de 1522 en 5º20'N, al SE de la isla de Palaos.

Para este trabajo ha resultado fundamental realizar un rastreo inicial de todas las islas existentes en el Pacífico en el entorno de las Islas Marianas. Solo así podremos saber con cuánta certeza estamos acertando o no a la hora de establecer cuáles fueron las islas visitadas en función de la información contenida en las fuentes.

DATO Nº3: Identificación de la isla de San Juan.

La carta incompleta y anónima en Torre do Tombo que atribuimos a Juan Bautista de Punzorol y León Pancaldo cuenta que "adelante de Maluco, obra de dozientas leguas, descobrimos dos yslas a las quales possimos nombre ysla de San Juan".

La identificación de estas islas resulta problemática, y cabrían dos hipótesis: que se trate de las mismas islas de Sonsorol anteriormente mencionadas, o que correspondan a Palaos (que cuenta con islotes menores adyacentes). Vamos a explicarlo:

La distancia de 200 leguas de Maluco coincide exactamente con Palaos, manteniendo los 5,5 km por legua que resultan del análisis de la derrota seguida en la primera vuelta al mundo, así como del Memorial atribuido a Magallanes dirigido al Emperador. En cambio, las islas de Sonsorol se encontrarían a solo 133 leguas de Maluco. Sería un error bastante abultado.

Es posible que el nombre asignado a esta isla de San Juan tenga correspondencia con el santoral vigente entonces. De ser así, el 6 de mayo de 1522 se celebraba en Roma el día de San Juan Damasceno (Fuente: Cappelli, Adriano. Cronologia, cronografia e calendario perpetuo, Ulrico Hoepi Editore. Milán, 2012). La distancia a cubrir resultante entre los días 3 y 6 de mayo, en que avistaran las islas de Sonsorol y la de San Juan, respectivamente, resulta razonable que pudiera ser cubierta por los de la Trinidad en tres días. Hablaríamos de 300 km en tres días.

Hay cartografía posterior al viaje que recoge la isla de San Juan, aunque lo hace en una latitud algo menor a la de Palaos (5º y medio o 6º N frente a los 7ºN de Palaos, aproximadamente). En realidad no hay ninguna isla en la latitud exacta indicada estos mapas. El primero en que encontré la isla de San Juan fue el planisferio de Sebastián Caboto, de 1544:

Recorte del planisferio de Sebastián Caboto del año 1544. En el centro, la ysla de San Juann, representada a 6º N. Mapa disponible en la BnF.

Dado que estoy lejos de ser experto en cartografía del siglo XVI, me puse en contacto con Luis Robles Macías, gran amigo y a quien tengo por un auténtico sabio en estas cuestiones y otras (una parte de su trabajo la expone en http://historiaymapas.wordpress.com). No tardó en enviarme otras tres obras cartográficas previas o coetáneas a la de Caboto, en que aparecía también la isla de San Juan, representada en todos los casos en el mismo lugar y latitud aproximadas. Los tres son mapas potugueses, sin fecha ni firma, y se suelen datar entre 1530 y 1540:

Representación de la isla de San Juan en diferentes cartas portuguesas. Información proporcionada por Luis Robles. De izquierda a derecha:

-

Atlas náutico en la Biblioteca Riccardiana (Florencia), Ricc. 1813, atribuido a Gaspar Viegas. Fecha estimada 1537. Imágenes digitales en MEDEA-Chart. En el f.8v aparece una isla “s: joam”, y en el f.9r, en la misma región, aparece una isla “sā joā”.

-

Atlas náutico en el Archivio di Stato di Firenze, CN 17. Atribuido también a Gaspar Viegas, muy similar en estilo y contenido al anterior. Fecha estimada 1534. Imágenes digitales en el ASF. En la p.15 aparece una isla “sanjoā”, y en la p.16, en la misma región, una isla “s: joā”.

-

Planisferio náutico en la Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Viena), E 21.009-15-D POR MAG11. Atribuido a Pero Fernandes. Fecha estimada 1545. Imagen digital en MEDEA-Chart. Las Molucas aparecen dibujadas dos veces, una a cada extremo del planisferio, y con ellas una isla llamada “i. de sam joam” en occidente (reproducida aquí) y “s. joam” en oriente.

Como podemos comprobar, la información sobre la isla de San Juan que obtenemos por cartografía es la misma, y la correlación con cualquier isla existente en este entorno no es sencilla porque, de tratarse de Palaos, hay un error de más de un grado en su latitud, mientras que en la posición indicada las únicas islas a las que podrían también corresponder son las de Sonsorol, que no son más que dos pequeños atolones.

Cabe comentar que la única expedición conocida que dio noticia del avistamiento de alguna isla en este entorno, posterior al viaje de la Trinidad, y previa a la datación de estos mapas, fue el segundo intento de tornaviaje de la nao Florida, la de Álvaro de Saavedra (obtuvimos su derrota en Google Maps aquí), que recorrió esta zona en septiembre de 1529. Según la relación de Vicente de Nápoles (A.G.I., Patronato, 43, N.2, R.11), quien fue uno de sus supervivientes, tras la muerte de Saavedra se decidió retornar al Maluco desde mitad del Pacífico, hallando en el camino una de las islas de Los Ladrones (Marianas), más adelante la isla de Disayn [probablemente actual Dinaey], que no pudimos tomar y pasamos de largo, y por último las islas de Taraole, questan de Maluco a ciento y veinte leguas. Según vemos, por esta información no encontramos motivos por los que fueran ellos quienes nombraran a una de estas islas como San Juan.

Por todo ello, aunque con reservas, nos inclinamos a pensar que los de la Trinidad avistaron las islas de Sonsorol el 3 de mayo, para cruzar en tres días hasta la de Palaos, nombrada como isla de San Juan por coincidir con el santorial, ubicada exactamente a las 200 leguas de Maluco que dieron como referencia, y de la que pasaron también de largo. Posteriormente, no recordaron con exactitud la latitud geográfica de Palaos, que quedó registrada en una altura algo inferor a la que le corresponde.

DATO Nº4: Identificación de la isla de Cyco.

Prosiguiendo con el viaje descrito en el Roteiro, el siguiente punto de referencia consiste en la isla que llaman de Cyco, "que está en diecinueve grados, a la cual llegaron el once de julio." Es decir que en cinco semanas han pasado de la latitud 5ºN a la 19ºN. Sin duda siguen con vientos que les impiden avanzar al Este. En esa latitud encontramos tres islas posibles, las más septentrionales del archipiélago de las Marianas.

¿Cuál de estos islotes corresponde a la que llamaron Isla de Cyco, en la que recaló la Trinidad? Según esta investigación, fue el Farallón de Pájaros, mientras que en los islotes de Maug fue donde huyó el célebre Gonzalo de Vigo, que pasó a vivir con los indígenas hasta que le encontró la Expedición de Loaysa.

El Farallón de Pájaros es la más al Norte de las tres islas y se encuentra en una latitud de 20º32'. La del medio resulta ser a su vez un grupo de tres pequeñas islas con forma de cráter, en 20º justos, y la isla más al sur es la llamada Asunción, que encontramos en 19º41'. En principio la que más se aproxima a los 19º que nos da el Roteiro es ésta última, la Isla Asunción, pero si seguimos leyendo encontramos una clave que nos indica que no es así.

Resulta que en la isla de Cyco "llevaron a un hombre que tomaron consigo.". El viaje proseguirá, pero cuando mucho más adelante toman la decisión de dar la vuelta a las Molucas tratarán de volver a esta isla. Y aquí prosigue el relato del Roteiro: "... y el hombre que llevaban que antes habían tomado en la dicha isla, les indicó que pasasen más adelante, que encontrarían tres islas donde tendrían buen puerto." Conclusión: avanzando desde Cyco encontrarán las tres islas de Maug. Por lo tanto, la isla de Cyco es el conocido hoy como Farallón de Pájaros. No hay dudas.

En estas tres islas de Maug el hombre que llevaban escapa. Quizás también fue aquí donde huyó Gonzalo de Vigo como veremos más adelante.

DATO Nº 5: El descubrimiento de las Islas Marianas.

El descubrimiento y recorrido a lo largo del archipélago de las islas Marianas no quedó referenciado en el Roteiro, pero sí en la carta de Gómez de Espinosa desde Cochín, y en las de los dos oficiales genoveses escritas en Mozambique:

"Sabrá vostra Sacra Majestad cómo descobrí catorce islas, las cuales eran llenas de infinitísima gente desnuda, la cual gente era de la color de la gente de las Indias; donde, Señor, tomé lengua para saber lo que había en ellas, y por no entender la lengua, no supe lo que había en estas dichas catorce islas. Señor, están desde doce grados hasta veinte grados de la parte del norte de la línea equinoccial, por lo cual señor, partí déstas el día de San Bernabé, siguiendo el dicho mi viaje." Carta de Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa al Emperador desde Cochín.

"Descobrimos catorze yslas dellas grandes y dellas pequeñas, a las quales alcançé el nonbre de la más parte dellas: la primera se llama Hora y no es poblada, y está en más de veinte grados; la otra se llama Maho, es poblada ella y todas las otras. La otra se llama Chenchón, la otra Grega, la otra Aramagán, la otra Anatán, la otra Baham, la otra Guguán, la otra Saepán, la otra Charega, la otra Derota." Carta incompleta y anónima atribuida a Juan Bautista de Punzorol y León Pacaldo desde Mozambique.

"A quinientas leguas de Maluco aviamos descubiertas quatorze yslas, las quales fuemos desta via a demandar, que ellas estan desde veinte grados hasta diez grados de la parte del norte." Carta de Juan Bautista de Punzorol y León Pancaldo desde Mozambique, dirigida al Emperador.

"A quinientas leguas de Maluco descobrimos quatorze yslas, las quales heran muy ben pobladas de jente desnuda. [...] Estas yslas señor son desde veinte grados hasta diez grados de la parte del norte, y demoran con las yslas de Maluco nordeste y sudueste." Carta de Juan Bautista de Punzorol y León Pancaldo desde Mozambique, dirigida a un Reverendísimo Señor.

Las catorce islas referidas son sin ninguna duda la cadena de islas del archipiélago de las Marianas, que discurre en dirección Norte- Sur formando un amplio arco, puesto que se encuentran desde los doce grados la más al Sur -Isla de los Ladrones, o Guam- hasta los 20 -Farallón de Pájaros-. No hay otra posibilidad. Son efectivamente 14 islas principales (algunas más si añadimos islotes muy pequeños), y sobre todo, no hay otras islas en esta zona entre las latitudes 12º y 20º.

Cabe aclarar que de estas 14 islas, la ubicada más al Sur ya había sido descubierta por la expedición previamente. Era la que habían llamado Isla de Los Ladrones, hoy Guam. Había sido la primera tierra que tocaron la Trinidad, la Victoria y la Concepción viniendo desde el Estrecho de Magallanes.

Las cartas de los genoveses referencian estas islas de norte a sur, por lo que debieron recorrerlas solo durante la vuelta. Resulta de especial interés la carta incompleta que les atribuimos, dado que nombra a la mayoría de ellas asignándoles topónimos que, en general se parecen mucho a los actuales. También cabe aclarar que a la más septentrional la llama Hora, y no Cyco como ocurría en el Roteiro. El planisferio de Sebastián Caboto ya mencionado recogerá la mayoría de los topónimos según esta misiva.

La cadena de 14 islas del archipiélago de las Marianas, que recorrió y descubrió la Trinidad durante el viaje de retorno a las Molucas.

DATO Nº 6: Las islas de Santa Heufemia.

Ninguna otra fuente las menciona, pero la carta incompleta que atribuimos a los genoveses cuenta que más adelante de la isla de San Juan, "obra de çien leguas, descobrimos otras ocho o nueve yslas no mucho grandes a las quales possimos nombre yslas de Santa Heufemia, las quales yslas estan en ocho grados y medio y en nueve de la parte del norte".

Si volvemos a dar por cierto que nombraran a estas islas por avistarlas el día de Santa Eufemia según el santorial vigente entonces, obtenemos que se trataría del 16 de septiembre. Según la cronología del viaje obtenida por el resto de fuentes, de ser así, tuvieron que avistarlas durante el regreso. Por la distancia dada respecto a la isla de San Juan y por la latitud aportada, pensamos que se trata del atolón Ngulu, ubicado en 8 grados y medio.

Al dar por buena esta referencia, obtenemos como consecuencia que el ritmo de avance de la nao Trinidad fue lento, al menos desde aquí hasta las Molucas, lo cual sería muy lógico si tenemos en cuenta la enorme cantidad de bajas que se sufrían por entonces, y el lamentable estado con el que llegaron, con solo seis personas hábiles para trabajar "que dieron la vida a los otros", y "con la vela a medio mástil por más no poder".

DATO Nº 7: La fecha de salida desde la cadena de islas de las Marianas

Decía Gómez de Espinosa que abandonaron estas islas el día de San Bernabé. Se trataría entonces del 11 de junio, aunque en el Roteiro se da la fecha del 11 de julio.

Nos vamos a quedar con la dada por el capitán, puesto que encajaría perfectamente con el resto de la cronología del viaje y los pequeños avances diarios obtenidos mientras navegaban con vientos contrarios.

DATO Nº 8: Las bajas

Otro factor a considerar lo encontramos en el listado de bajas que se produjeron en la travesía. Resulta que todos se mantuvieron vivos hasta el 10 de agosto, fecha en que falleció el calafate Juan González. Los días 24 y 29 de agosto murieron Marcos de Vayas, barbero (es decir, el médico, una pérdida importante) y el 29 Alberto, sobresaliente. Pero es que en septiembre el ritmo de muertes se aceleró de forma terrorífica, con 12 fallecidos, y esto continuaría siendo así hasta el 30 de octubre, con otras 15 personas. El viaje terminó en las Molucas a finales de octubre.

Esto es muy importante, no solo para darnos cuenta de lo dramática que fue la situación de aquel barco, sino también para poner de relieve que a partir de mediados de agosto los víveres eran ya muy escasos, es decir, que llevaban ya tiempo sin poder avituallarse en tierra. Y que esta situación se mantuvo hasta el 30 de octubre, coincidiendo con el fin del viaje.

DATO Nº 9: La huida de Gonzalo de Vigo

Este asunto es quizá el menos claro de todos los tratados por las fuentes debido a las discrepancias que encontramos entre ellas. Quizá la fuente que más detalles nos aporta, y por lo tanto parece más fiable, es la relación de fallecidos. En ella se nos da como fecha de la huida "fin de agosto" y se nos proporciona los nombres de los dos hombres que acompañaron a Gonzalo de Vigo: Alonso González y Martín Genovés.

Esta fecha es muy importante, porque es la única referencia cronológica de lo sucedido después de que hubieran tomado la difícil decisión de dar la vuelta y poner rumbo de nuevo hacia las Molucas.

El Roteiro omite esta huida. No obstante, sí trata en cambio sobre del un isleño al que habían tomado durante el viaje de ida, sobre la cual ya nos hemos referido antes, y llegado a la conclusión de que este hecho se produjo en la isla de Maug, sin dar fecha, pero sí dejando claro que se trataba de la segunda vez que pasaban por la isla cercana del Farallón de Pájaros, es decir, en el viaje de vuelta: "en una isla que primero descobrimos y tornamos a arribar a ella con temporal".

En cambio Ginés de Mafra sí se refiere de modo muy sucinto a la huida de Gonzalo de Vigo, pero lo hace diciendo que fue durante el viaje de ida, y que se produjo en la isla de Guam, o Isla de Los Ladrones, que está en 12ºN. Hay que decir además que fue justamente aquí donde la Expedición de Loaysa encontró a Gonzalo de Vigo. Éste terminará siendo uno de los supervivientes de la expedición, porque se integrará en la vida de los indígenas. Sabemos de él porque se presentará a los de la expedición de Loaysa cuando arriban a la isla de Guam, en un hecho realmente increíble, y se unirá a ellos como traductor desarrollando un importante papel en los sucesos que tuvieron lugar después en las Molucas. Eso sí, nunca volvió a España. Según contó sus dos compañeros terminaron muertos al poco de su huida por ciertas sinrazones que cometieron.

Si damos por buena la fecha de finales de agosto en que se produjo la huida de Gonzalo de Vigo según la relación de fallecidos -y no hay ningún motivo por el que no hacerlo- sería imposible que ésta tuviera lugar en la isla de Guam como dice Ginés de Mafra, sino en la isla de Maug, en la parte más septentrional de las Islas Marianas. Para haberse producido en Guam, ubicada mucho más al Sur, habría sido necesario que transcurriera más tiempo. En todo caso, Mafra habla de que huyeron en la ida, lo cual está descartado por la cronología obtenida a través del resto de fuentes. Es imposible que sean coherentes las versiones de Mafra y de la relación de fallecidos, debiendo quedarnos con ésta por concordar con el resto de datos que tenemos.

CONCLUSIONES: Cronología y ruta seguida con mayor probabilidad

-

Zarpan de la isla de Tidore (Islas Molucas) el 6 de abril de 1522, con 55 tripulantes.

-

Costean la isla de Halmahera hacia el Norte, (a Halmahera la llaman isla de Batechina o de Gilolo).

-

Doblan el cabo más septentrional de esta isla, y continúan costeando, esta vez en dirección Sur, hasta detenerse en una población que llaman Quimor. Posiblemente corresponda con la ciudad que los de la expedición de Loaysa conocieron como Zamafo, llamada hoy Tobelo.

-

En Quimor se abastecen durante algunos días, zarpando el 20 de abril de 1522.

-

Toman rumbo Este hasta salir del archipiélago de las Molucas, muy pocos días, y desde entonces los vientos les son contrarios de forma constante, debiendo desviarse al Nordeste para poder avanzar.

-

El 3 de mayo de 1522 descubren dos islotes en 5ºN, que corresponden casi con total certeza a dos atolones del archipiélago de Sonsorol.

-

El 6 de mayo de 1522 descubren Palaos, y continúan sin detenerse rumbo al NNE.

-

El 11 de junio de 1522 arriban al Farallón de Pájaros: la isla más septentrional del archipiélago de las Marianas. Aquí toman consigo a un nativo.

-

Avanzan siempre con dirección NNE por mantenerse los vientos contrarios. Los vientos en estas latitudes son más fuertes.

-

El 10 de agosto, se produce la primera muerte, con el fallecimiento de Juan García.

-

A mediados de agosto les sobreviene un fuerte temporal, de 12 días de duración, que les destroza el castillo de popa y causa otros daños graves. Durante el temporal se hace muy difícil preparar comida, enfermando la mayoría de la tripulación. Por entonces los víveres se limitan ya únicamente a arroz.

-

El temporal les sobreviene a la latitud de 42ºN, a una distancia estimada de las islas Molucas de 500 leguas -2.750 km- en sentido Este-Oeste.

-

Con el temporal deciden renunciar a seguir avanzando, tomando rumbo de vuelta hacia las Molucas. Avanzan hacia el SSO muy rápidamente.

-

A finales de agosto vuelven a la isla de Cyco (Farallón de Pájaros). El isleño que habían tomado consigo en la ida les advierte de que si avanzan al Sur encontrarán muy cerca un grupo de tres islas donde les será más fácil tomar tierra. Siguen su recomendación, encontrando así las tres islas que llaman Mao, actualmente denominadas Maug. En ellas huyen Gonzalo de Vigo, Alonso González, Martín Genovés y el propio isleño.

-

Continúan viaje hacia las Molucas produciéndose una tremenda sucesión de bajas por enfermedad. Recorren la cadena de 14 islas de las Marianas, aunque es evidente que no por ello consiguen reabastecerse y mejorar así la salud de la tripulación. Antes al contrario, es posible que ante la debilidad general ni siquiera se arriesgaran a tomar tierra en ellas exponiéndose a algún enfrentamiento con los nativos.

-

El 16 de septiembre avistan las "yslas de Santa Heufemia", que identificaríamos con el atolón Ngulu.

-

El 31 de octubre de 1522 se produce el último fallecimiento: Jerónimo García. Han muerto en el mar nada menos que 31 hombres.

-

A finales de octubre recalan en la isla aledaña de Doyz, conocida como Pulau Doi. Los portugueses ya estaban en la isla de Ternate, bajo el mando de Antonio de Brito, y pronto les apresan. La Trinidad se va a pique frente a la fortaleza de Ternante antes de ser descargado el clavo que transportaba.

-

De los hombres que consiguen volver a las Molucas, más los que habían quedado al cargo de un almacén en Tidore, tras ser apresados por los portugueses 10 de ellos morirán. Al cabo del tiempo 3 de ellos quedarán libres en Malaca, y uno de ellos como esclavo. De dos ellos no sabemos qué pasó, y los cinco restantes son los que consiguieron volver 5 años después: Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa, Ginés de Mafra, León Pancaldo y Juan Rodríguez "El Sordo" -este un año antes- y Hans Vargue, quien murió todavía preso en Lisboa.

Comparación del viaje de la Trinidad con el tornaviaje de Urdaneta

Andrés de Urdaneta fue el primero que consiguió la vuelta de Asia hasta América a través del Pacífico, el llamado Tornaviaje, con el que pasó a la Historia. Lo hizo en el año 1565, después de muchos intentos fracasados. En general, los intentos anteriores no encontraron vientos favorables por no haber navegado lo suficientemente al Norte, hasta alcanzar la corriente de Kuro-Siwo que, de modo parecido a como en el Atlántico hace la Corriente del Golfo, favorece la navegación en sentido Este.

He querido comparar la ruta seguida por Urdaneta con la que aquí hemos determinado como más probable que siguió la Trinidad de Espinosa, y este es el resultado:

Comparación del tornaviaje de Urdaneta, siguiendo día a día su derrotero en Google Maps, con la ruta probable seguida por la Trinidad. Ambas derrotas se solapan en la zona donde a Urdaneta le entraron vientos favorables para dirigirse a América. Los de la Trinidad no tuvieron esa suerte, aunque lo habían hecho durante los mismos días del año que Urdaneta.

Pincha en la imagen para acceder al Derrotero del Tornaviaje de Urdaneta en Google Maps.

Vistas del Derrotero del Tornaviaje de Urdaneta en Google Earth. Para descargar el archivo .kmz pincha AQUÍ.

Como vemos, Espinosa tuvo en la mano conseguirlo. Incluso hay un buen tramo en que se solapan ambas rutas. En su caso, no tuvo la suerte de encontrar vientos hacia el Este donde Urdaneta sí lo hizo, y tuvo que proseguir aún más que él hacia el Norte. Además, esto ocurría no solo en la misma zona geográfica sino también en los mismos días del año. Con ello, lejos de restar mérito al grandísimo Urdaneta, lo que pretendemos es poner en valor lo que hicieron Espinosa y sus hombres con la Trinidad, porque ellos también encontraron el camino, aunque la suerte les fue esquiva.

Les recomiendo la conferencia de Braulio Vázquez en el Archivo General de Indias acerca del intento de vuelta de la nao Trinidad, y de lo que sucedió a la tripulación superviviente a la travesía después de ser apresada. Y doy las gracias a Braulio, por tantos y tantos ratos que hemos disfrutado juntos tratando de averiguar lo que ocurrió.

Y también les invito a ver la conferencia on-line sobre el capitán Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa que tuve ocasión de dar para la Fundación VIII Centenario de la Catedral de Burgos, en marzo de 2020.

Para completar la visión de este episodio del viaje, por favor visiten la sección Matemáticas de Magallanes, donde encontrarán una hipótesis sobre por qué eligieron la vuelta por el Pacífico.